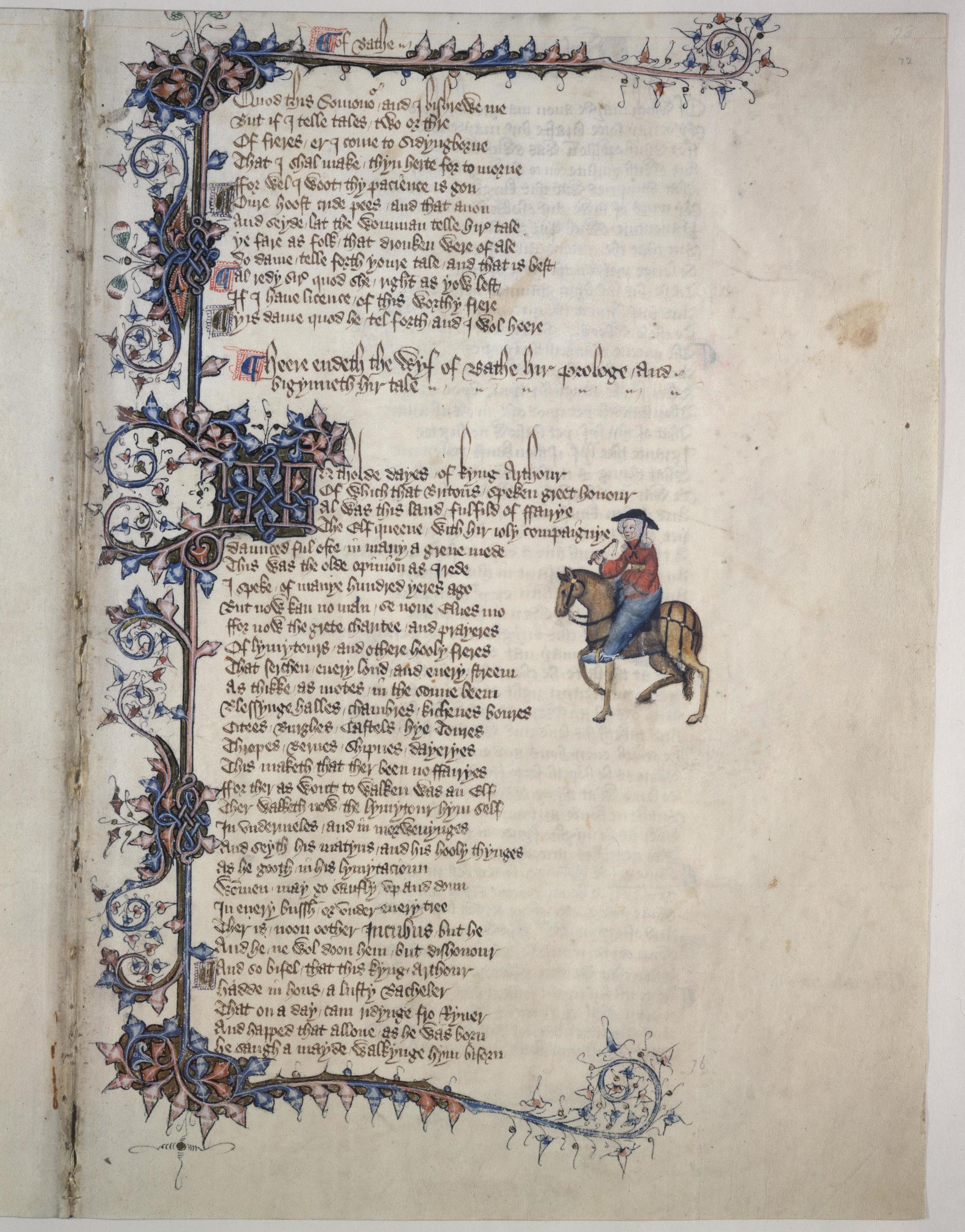

But prior to Barnum, Geoffrey Chaucer gave us both a snake oil salesman and a snake charmer in the Pardoner and the Wife of Bath in his The Canterbury Tales. The Wife of Bath may not be a snake charmer in the traditional sense, but she might try to charm a snake out of its skin, or at least his clothing. The Pardoner may not charm the snake at all, but he’ll sell you both its oil and its skin, and make you believe you’ll go to heaven in the bargain.

Betwixt the two, we find two exemplas, the moral tales which were popular in Medieval times.

Ladies first, if Alisoun may be called a lady. In this Wife of Bath’s quite lengthy prologue we learn of her five husbands as well as her Biblical justification for having had so many. We also hear of her poweress both in marriage and in the marriage bed. For this reason, the tale is usually grouped with the Clerk’s, Merchant’s, and Franklin’s tales in the Marriage Group. Another division is sometimes preferred by scholars which separates the stories with moral issues from those that deal with magical issues, placing her tale in the later group.

But the Wife of Bath’s tale seems to live in both worlds, the moral and the magical. Enchantress that she is, the Wife of Bath may be using the subject of magic to empower her tale about making a moral choice; her superstitious audience might be charmed more easily if magic turns the tale’s pages. Although the tale’s moral isn’t of a religious nature, the moral Alisoun implies is clear; the woman should reign supreme in marriage.

So they lived ever after to the endExemplas would have been used by Medieval preachers to enhance their sermons, driving home a moral conclusion or illustrating a point of doctrine. With this definition, The Wife of Bath’s Tale might not be considered an exempla at all. But it could be argued since Chaucer made Alisoun’s prologue twice as long as her tale, and since in it she frequently reinforced her idea of female dominance with the teachings of Christ and the Apostles, that she did use her story to enhance her own doctrine of life, love, and marriage.

In perfect bliss; and may Christ Jesus send

Us husbands meek and young and fresh in bed,

And grace to overbid them when we wed.

And – Jesu hear my prayer! – cut short the lives

Of those who won’t be governed by their wives;

And all old, angry niggards of their pence,

God send them soon a very pestilence!

(292, Penguin)

The message behind the Pardoner’s tale is clearly moral, but less obvious is the irony created by the person of its teller; after the Pardoner’s self-revelation he seems an unlikely preacher against avarice. The Pardoner admits to using his position within the Roman Catholic Church to extort the poor and helpless, pocket indulgences, and generally fail to abide by the church's teachings on jealousy and avarice.

The Pardoner’s Prologue contains a confession similar to details the Wife of Bath gives away about herself in her own prologue. His mention of a “draught of corny strong ale” might suggest he is being so open because he is drunk, but this is not 100% clear.

Unlike the Wife of Bath, the Pardoner is sexually deficient. Prior to his tale, in the general prologue, the Pardoner is described as beardless with a small goat-like voice. The narrator concludes the Pardoner is either a gelding eunuch or a mare (effeminate), but more importantly these descriptions draw parallels between his sexual deficiency and his spiritual deficiency. The Pardoner is like a travelling salesman, seeking to set himself up as the ultimate source for religious relics. But just as his relics are spiritually impotent, so is this impotent man.

While Chaucer wrote powerful exemplas in his Pardoner and Wife of Bath tales, the irony between their content and their respective narrators castrates their intrinsic message and leaves both impotent. The Wife of Bath may seem an early champion of women's rights, but her excesses leave one to question her motives. The Pardoner may find a following to hear his spiritual message, but his material indulgences leave that message nearly as impotent as his physical self.

Nevertheless, these tales and prologues are insightful enough to enhance discourses on religion as well as discourses on human nature, even if it is at the expense of those who tell them.

No comments

Post a Comment